Godzilla’s eternal reign as the King of Monsters is no accident-it’s the result of decades of subtle yet impactful design tweaks that have kept the iconic kaiju fresh and formidable. From the original 1954 suit’s bulky, amphibious look inspired by dinosaurs to the sleek, jagged forms of modern CGI renditions, every tiny change in Godzilla’s appearance has helped evolve the character while honoring its roots. These incremental transformations, such as the shifting number of toes, the size and shape of dorsal plates, and the color and texture of his skin, have ensured that Godzilla remains a timeless symbol of power and resilience in cinema.

The Godzilla that first debuted in 1954 looks way different than the one we see in 1974 or 1994 or 2014, and with the proliferation of Godzilla media hitting us this year, like Apple TV Plus’ Monarch: Legacy of Monsters and Toho’s Godzilla Minus One, there’s never been a better time to dive deep into the many styles of the world’s favorite nuclear reptile.

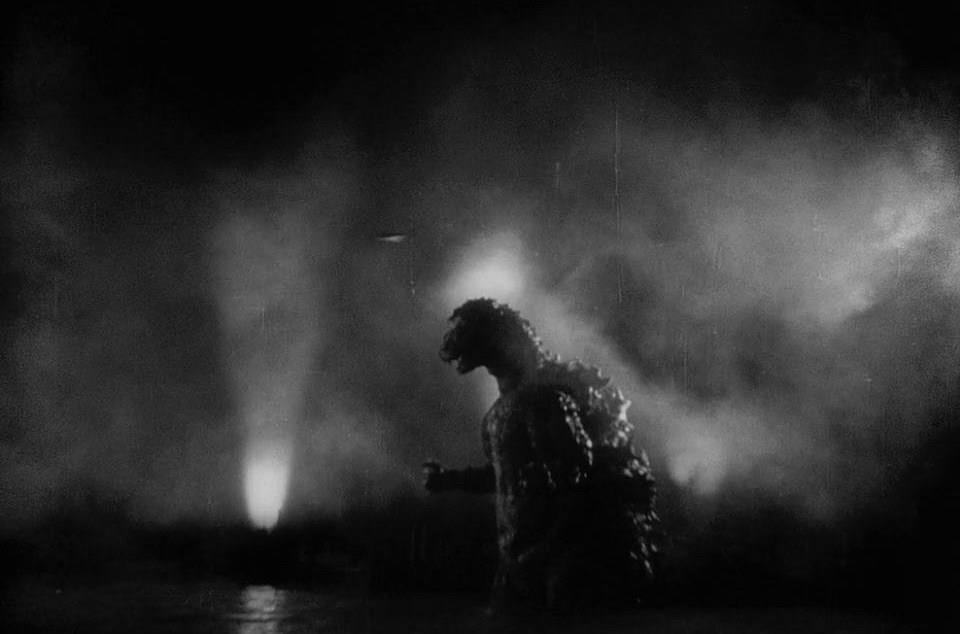

Godzilla (1954)

Godzilla (1954) is a landmark Japanese kaiju film directed by Ishirō Honda, featuring groundbreaking special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya. The story centers on a prehistoric monster awakened by nuclear testing, wreaking havoc on post-war Japan and embodying the nation’s fears of nuclear destruction. The film pioneered the “suitmation” technique, with an actor in a monster suit interacting with miniature sets, and it launched the long-running Godzilla franchise, which has become a global pop culture icon. Initially released in Japan in 1954, it was later adapted into a heavily edited American version, Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), which introduced the character to Western audiences. The original film is praised for its thematic depth and innovative effects, influencing both Japanese tokusatsu cinema and international monster movies.

Brought to life with a blend of suitmation and puppetry (and becoming the godfather of the Japanese tokusatsu genre), the first Godzilla is a menacing creation. Stocky and scarred, this Godzilla is built for an unstoppable stomping charge across Tokyo (his arms are fairly immobile, a feature that won’t be revisited until the 2016 reboot, Shin Godzilla). Every movement feels deliberate, and many shots are devoted to the thick legs and feet plowing through buildings. However, not all of this was pure cinematic intention: Suit actor Haruo Nakajima suffered and sweated under a 100-kilogram suit made of inflexible material.

Godzilla Raids Again (1955)

“Godzilla Raids Again” (1955) is the first sequel to the original 1954 “Godzilla,” continuing the story with a new threat as a second Godzilla emerges and battles the monster Anguirus, leading to widespread destruction in Osaka. Unlike the first film, which symbolized the horrors of nuclear war, this sequel reflects the struggles of post-war recovery and the ongoing fear of atomic weapons. The film features intense monster battles and notable special effects by Tsuburaya, with the Japan Self-Defense Forces ultimately managing to bury Godzilla under ice to halt his rampage. Though less allegorical than its predecessor, the original Japanese version is regarded as a compelling and classic 1950s monster movie, praised for its symbolic message and impactful scenes.

The suit for the first Godzilla sequel is markedly different from the original: It’s much leaner, with a thinner neck and legs and a head that looks extremely goofy when viewed from the front (the puppet work also takes a hit here). Much of this is due to Godzilla now having to wrestle with his first kaiju nemesis, the four-legged Anguirus. Since many of the films going forward would inevitably revolve around a colossal MMA match, the Big G had to get leaner, more nimble, and more openly emotional. The suits had to reflect all of Godzilla’s little triumphs and frustrations now, moving away from the apocalyptic presence in the 1954 film.

King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962)

The 1962 film King Kong vs. Godzilla is a landmark in monster cinema, featuring the iconic clash between two legendary titans. The story revolves around a pharmaceutical company’s attempt to boost TV ratings by capturing King Kong, while Godzilla is reawakened by an American submarine trapped in an iceberg. The film builds to an epic showdown on Mount Fuji, where the two monsters battle fiercely, with Kong gaining an unusual power boost from electricity. Despite some criticism for its lighter tone and limited Godzilla screen time, the movie remains a nostalgic and entertaining spectacle, showcasing the enduring appeal of both monsters in popular culture.

Whereas the first two Godzilla suits bore all of the scars and irregularities that would occur to a Tyrannosaurus rex-esque monster that was revived by nuclear weapons, this suit begins an era of streamlining. It’s more inherently reptilian (probably in an attempt to differentiate it from its primate foe, King Kong) and its arms and legs are brawny and combat-ready. It came in handy during the battle scenes – while the brawls in Godzilla Raids Again are frenetic and animalistic, King Kong vs Godzilla was inspired by the muscular antics of Japanese pro wrestling.

Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964) and Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964)

In 1964, Toho released two landmark films that expanded the Godzilla universe with iconic monster battles. Mothra vs. Godzilla features the divine moth Mothra defending Japan against Godzilla’s destructive rampage, culminating in a fierce battle where Mothra sacrifices herself to protect her egg, which later hatches into twin larvae that ultimately subdue Godzilla. This film marked the last time in the Shōwa era that Godzilla was portrayed purely as an antagonist and introduced themes of unity and moral judgment against greed and destruction. Later that same year, Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster introduced King Ghidorah, a powerful extraterrestrial dragon and Godzilla’s arch-nemesis, setting the stage for epic multi-kaiju confrontations that would become a staple of the franchise. Ghidorah’s design and alien origins have evolved over time, but its debut cemented it as a formidable foe alongside Godzilla and Mothra. Together, these films enriched the Godzilla mythos with complex monster dynamics and enduring character designs.

Godzilla’s fourth suit is a marvel – it’s sleek enough that Godzilla can roll and wrestle (and be physically outmatched by the three-headed space dragon King Ghidorah and go toe-to-toe with the graceful Mothra), but its face and eyes speak pure malice in a way that hadn’t been achieved since the first film. Nakajima, at this point, had perfected his Godzilla walk and fighting stance, keeping his arms slightly raised at the side and his palms facing slightly outward. It looks akin to sumo in a way, defining Godzilla as ready for all challengers.

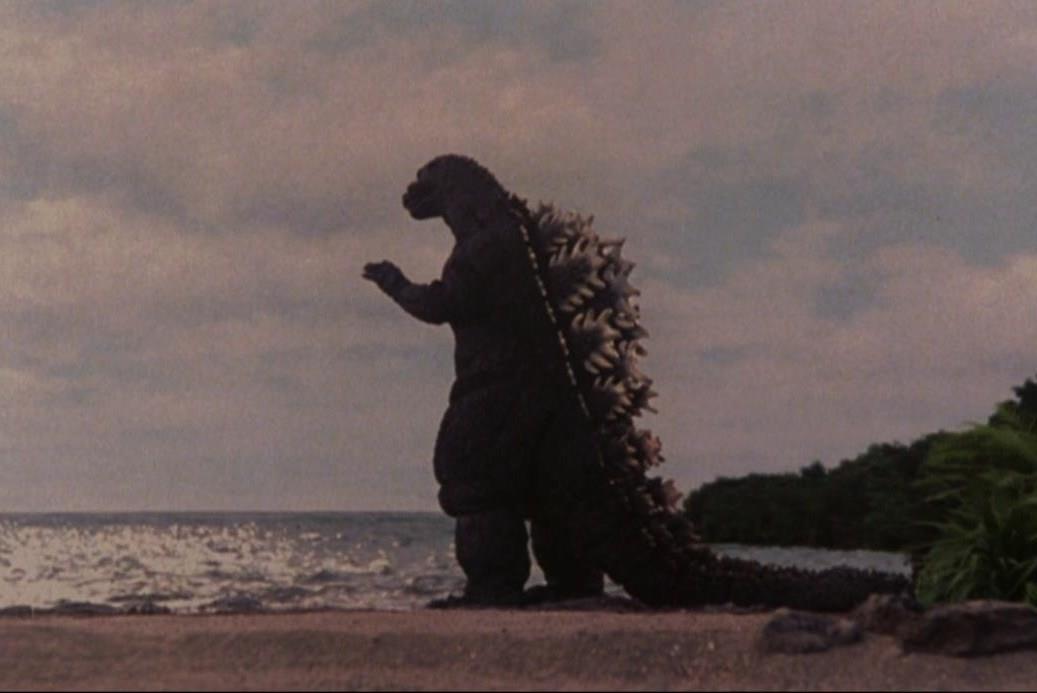

Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965) and Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966)

Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965) and Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966) represent a fascinating era in the Godzilla franchise where the series embraced more imaginative sci-fi elements and diverse monster battles. Invasion of Astro-Monster, directed by Ishiro Honda, features astronauts traveling to Planet X to help an alien civilization by enlisting Godzilla and Rodan to fight the menacing King Ghidorah, blending space adventure with classic kaiju action. This film is notable for its blend of monster battles and a quirky alien plot, showcasing Godzilla as a heroic protector and delivering mid-60s special effects charm. Ebirah, Horror of the Deep, meanwhile, takes a different approach, focusing on a tropical island setting and pitting Godzilla against the giant lobster monster Ebirah, adding variety to the monster roster and emphasizing more grounded, albeit still fantastical, scenarios. Together, these films highlight how subtle design and narrative shifts kept Godzilla fresh and relevant during the 1960s.

As it became more apparent that Godzilla films were adored primarily by children and monster movies began to compete with similar offerings available on TV, Godzilla’s design became a bit less scary. The mid-’60s would see an overhaul in the Big G – he retains his skinnier form, but has very little musculature (this makes Nakajima sometimes look like he’s wearing a big, rubber bag whenever he pops out of the water). His head becomes a friendlier circle shape and his eyes bulge, froglike, from the top of his skull. This is no longer a monster that seeks to destroy Tokyo. In fact, until the mid-’80s, Godzilla wouldn’t be wrecking much of anything again unless, of course, he was under alien control.

Son of Godzilla (1967)

Son of Godzilla (1967) is a tokusatsu kaiju film directed by Jun Fukuda that introduces Godzilla’s son, Minilla, amidst a backdrop of scientific weather experiments on a remote island. The experiments inadvertently cause giant mantises, known as Kamacuras, to grow to enormous sizes, leading to the discovery of a giant egg that hatches into the infant Godzilla. The film shifts Godzilla’s role from city destroyer to a protective father figure as he defends and raises Minilla while battling the monstrous insects. Despite a smaller budget and mixed reception, the movie is notable for its unique premise and the introduction of new kaiju characters, contributing to the enduring Godzilla legacy through subtle design and narrative changes.

With a head seemingly built to express annoyance at his new offspring, Minilla (at this point, the Godzilla headpieces now often included movable eyes and eyelids, anthropomorphizing the titan further), this suit isn’t much to write home about. Seeing as Godzilla is now a parent with a doughy little youngling to take care of, his oddly humanoid face makes sense here. But it inherits all of the problems from the previous suit as well and looks good at no angle.

Destroy All Monsters (1968), All Monsters Attack (1969), Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971), and Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972)

The films Destroy All Monsters (1968), All Monsters Attack (1969), Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971), and Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972) mark a significant phase in the Showa era of the Godzilla series. Destroy All Monsters was originally planned as the final Godzilla film and features the largest roster of monsters in the Showa era, showcasing Godzilla as a heroic figure among many kaiju. Following this, All Monsters Attack uniquely reuses and re-edits stock footage from previous films to create new monster battles, emphasizing thematic depth and the relationship between Godzilla and Minilla. Godzilla vs. Hedorah introduced an environmental message with Godzilla battling a pollution-based monster, while Godzilla vs. Gigan continued the trend of Godzilla facing off against formidable new foes, reinforcing his role as Earth’s protector. These films collectively illustrate Godzilla’s evolution from destructive force to heroic defender, supported by creative design changes and storytelling innovations throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s.

A brief return to form for Godzilla, this suit was originally planned to be the final one. A drop in box office had led Toho to assume that Destroy All Monsters would be an all-out kaiju slugfest finale to the series. And this suit, with its more defined features and domineering lizard-y face, makes Godzilla the perfect general for an army of monsters. It wasn’t the end, though, and Godzilla would continue in this suit for three more features. (By the end, though, its long tenure is evident. The suit is literally tearing apart on screen.) Godzilla vs. Gigan would be the end of Nakajima’s spectacular run as the monster – he’d be laid off by Toho after the film, among other contracted actors, in a cost-cutting effort.

Godzilla vs. Megalon (1973), Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla (1974), and Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975)

The early 1970s Godzilla films, including Godzilla vs. Megalon (1973), Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974), and Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975), marked a distinctive era in the franchise characterized by inventive monster designs and evolving storytelling. Godzilla vs. Megalon introduced the undersea civilization of Seatopia and the robot Jet Jaguar, culminating in a dynamic team-up between Godzilla and Jet Jaguar against Megalon and Gigan, blending sci-fi elements with kaiju action. The subsequent Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla brought in the iconic Mechagodzilla, a mechanical doppelgänger built by alien invaders, which became one of Godzilla’s most enduring foes due to its menacing design and array of weapons. Finally, Terror of Mechagodzilla served as a darker and more atmospheric conclusion to this phase, featuring a weathered Mechagodzilla and introducing new monsters like Titanosaurus, with practical effects and city destruction scenes that many fans still praise for their tangible realism and impact. Together, these films reflect a period of creative experimentation and gradual tonal shifts that helped sustain Godzilla’s lasting appeal.

Bearing the exaggerated eyes of prior suits from the mid-’60s, this Godzilla is certainly aimed to be a pal to its adolescent audiences and the precocious kid that takes center stage in Megalon. Thankfully, though, the suit was trimmed up a bit, which means it doesn’t get as baggy here, and when it came time for Godzilla to face Mechagodzilla, adjustments were made to the face to enhance its ferocity. It was a sense of rage that he’d need if he wanted to beat down his robot doppelganger, the most fearsome foe that had been introduced since King Ghidorah. Godzilla would be portrayed by three different suit actors across these three films.

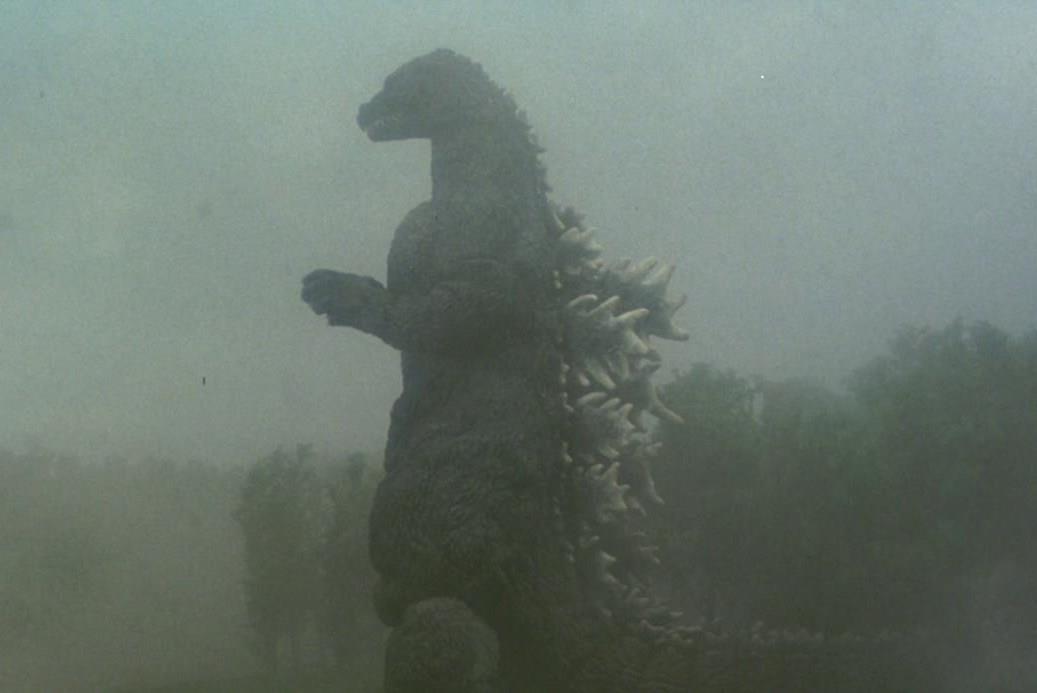

The Return of Godzilla (1984)

The Return of Godzilla (1984) marked a significant reboot of the Godzilla franchise, returning the character to its darker, more serious roots as a metaphor for nuclear devastation. The film follows the reawakening of Godzilla after a volcanic eruption near Daikoku Island, leading to a secretive Japanese government attempt to contain the threat. The story escalates as Godzilla attacks a Soviet nuclear submarine, sparking Cold War tensions and forcing international powers to confront the monster. The climax features Godzilla’s destructive rampage through Tokyo and a battle with the military’s advanced weapon, the Super X, culminating in Godzilla being lured back to a volcano and trapped by a controlled eruption. This film reestablished Godzilla as a symbol of both terror and a sobering reminder of humanity’s nuclear dangers, influencing the tone of subsequent entries in the series.

The beginning of the Heisei era of Godzilla films also brought with it a new consistent suit actor: Kenpachiro Satsuma. An admirer of Nakajima’s (he’d played Hedorah across from him in the 1971 film), Satsuma would deliver on the studio’s wishes of a more serious, dangerous Godzilla. The suit here reflects that: Godzilla has fangs for the first time since 1955, and the bagginess of many of the previous suits has been replaced by scaly bulk. Too much bulk, possibly, as Satsuma recalled feeling a bit swamped in a suit made for a larger man. In some shots, the suit is replaced by a “cybot,” a mechanical Godzilla that looks downright villainous and was mostly used for promotional purposes.

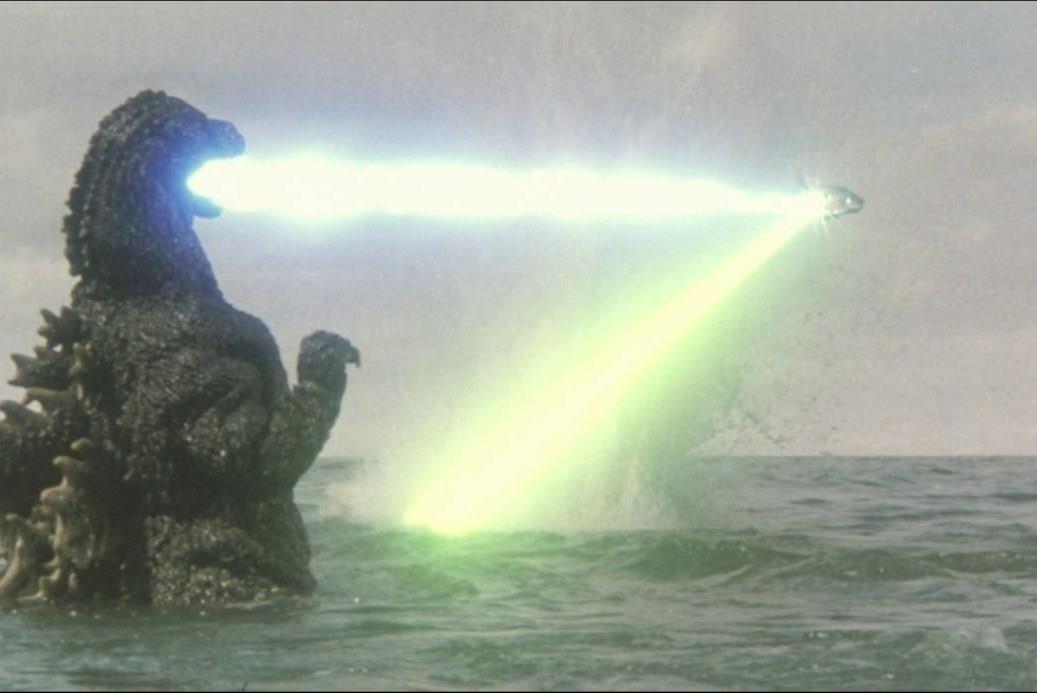

Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989) and Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991)

Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989) presents a unique and poignant story where a grief-stricken scientist creates Biollante, a monstrous hybrid born from Godzilla’s DNA combined with that of a rose and the scientist’s deceased daughter. The film explores themes of loss and scientific hubris as Godzilla battles this eerie plant-like creature, culminating in a dramatic showdown that tests Godzilla’s resilience and introduces innovative special effects. Following this, Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991) shifts gears to a more action-driven narrative involving time travel and the reimagining of King Ghidorah as a genetically engineered creature from the future. This film marks a return to classic kaiju battles, featuring intense monster fights and a subplot reflecting on Godzilla’s historical impact, though it embraces a more chaotic and less coherent storyline compared to its predecessor. Together, these films showcase the evolving design and storytelling approaches that have kept Godzilla relevant and captivating through the years.

As Godzilla went back into monster combat mode, his suit would change as well. It’s the most reptilian that Godzilla has looked since the early ’60s, with obvious chest muscles (this Godzilla looks like he could bench press a city) and meaty legs. However, unlike the earlier Godzilla films, where the monster was frequently seen tumbling during battle, Satsuma and the filmmakers tend to keep this era’s Godzilla as a more stoic conqueror. As such, an emphasis on laser beams and elaborate transformations replaced the outsized wrestling matches. It was such a good-looking Godzilla suit that it would even be stolen.

Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992)

Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992) marks a significant entry in the Heisei era of Godzilla films, reintroducing the beloved kaiju Mothra after a 24-year absence. The film features a three-way battle involving Godzilla, the divine Mothra, and her darker counterpart Battra, awakened by a meteorite impact. The story explores themes of environmentalism and the human threat to Earth, with Mothra and Battra initially at odds before uniting to confront Godzilla. Known for its improved special effects and dynamic monster battles, the film blends fantasy elements with classic kaiju action, showcasing Mothra’s transformation from larva to imago and the dramatic alliance against Godzilla. Directed by Takao Okawara, it balances thrilling fight sequences with a deeper lore for Mothra, making it a memorable chapter in the franchise’s evolution.

Unlike the Showa-era suits, the Heisei Godzilla suits require a bit more magnification in order to spot their differences from film to film. For instance, the one here looks a lot like the previous movie’s, except it’s a bit slimmer with an abbreviated snout and noticeably weaker shoulders. It’s the same design tactic they used the first time Godzilla had to take on Mothra nearly 30 years earlier, though Godzilla might’ve needed the size advantage here. He had to take on Mothra’s dark twin, Battra, too.

Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla II (1993)

Godzilla vs. MechaGodzilla II (1993) showcases a renewed battle between Godzilla and a high-tech Mechagodzilla, this time created by the United Nations Godzilla Countermeasures Center using parts from Mecha-King Ghidorah. The film introduces Baby Godzilla, a juvenile Godzillasaurus with a telepathic link to Godzilla, whose presence draws both Godzilla and Rodan into conflict. Mechagodzilla, equipped with an array of advanced weaponry and capable of merging with the aerial gunship Garuda to become Super-Mechagodzilla, initially gains the upper hand. However, Rodan sacrifices himself to restore Godzilla’s strength, enabling Godzilla to destroy Mechagodzilla and reunite with Baby Godzilla. This installment is notable for its updated monster designs and the shift of Mechagodzilla from alien control to a human-made weapon, marking a key evolution in the franchise’s design and narrative continuity.

Once again, the details shift only slightly here: The most significant alteration is the amount of bulk Godzilla seems to be carrying. He’s a bit heavier here, all the more ready to take on Mechgodzilla’s array of weaponry and keep standing.

Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla (1994) and Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995)

The 1994 film Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla introduces a formidable extraterrestrial foe born from Godzilla’s own cells exposed to a black hole’s radiation. SpaceGodzilla arrives on Earth with the intent to destroy Godzilla and conquer the planet, leading to intense battles featuring the new defense robot M.O.G.E.R.A. and psychic Miki Saegusa. The film is notable for SpaceGodzilla’s unique crystalline design and malevolent personality, marking one of Godzilla’s most vicious adversaries. The climax centers on Godzilla’s strategic use of his energy to overload and defeat SpaceGodzilla, though the creature’s essence escapes into space. Following this, Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995) serves as a dramatic and somber milestone in the franchise, featuring a powerful and deadly opponent linked to the original Godzilla’s atomic origins. This film is remembered for its darker tone and the significant impact on Godzilla’s legacy, underscoring the series’ evolution through design and storytelling changes that keep the King of Monsters eternally relevant.

There isn’t really a weak suit in the Heisei era, and they culminate nicely here. Though SpaceGodzilla is generally regarded as a pretty weak film, Destoroyah is a nice callback to Godzilla’s atomic roots and serves as a poignant (temporary) ending for the King of the Monsters as he experiences an internal meltdown. The red and orange lights added to the suits make for a striking, burning image, and Satsuma regards it as his best performance, adding grueling pathos to the kaiju.

Godzilla (1998)

Godzilla (1998)

The 1998 American adaptation of Godzilla marked a dramatic departure from the creature’s classic design, introducing a sleeker, iguana-inspired monster born from French nuclear testing in Polynesia. This Godzilla rampages through New York City, evading the military and spawning hundreds of eggs in Madison Square Garden, emphasizing a new focus on speed, stealth, and asexual reproduction. While the film’s reimagined look and narrative sparked controversy among longtime fans for straying from Toho’s traditional Godzilla iconography, it remains a pivotal moment in the franchise’s evolution-demonstrating how even radical design changes can keep the King of the Monsters relevant for new generations.

The famously maligned Godzilla from TriStar Pictures gives us perhaps the greatest remix that the monster has ever received. An irradiated marine iguana, this Godzilla is hunched over in a more modern dinosaur pose with its thick legs replaced by lean sprinter’s muscles and his back plates jutting at different angles. In the film, it’s a fairly graceless creature, but its tie-in animated series turned it into a fierce and agile combatant.

Godzilla 2000: Millennium (1999) and Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (2000)

Godzilla 2000: Millennium (1999) and Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (2000) showcase the King of the Monsters with a consistent design, as the latter reused the Millennium suit, leading to confusion among fans about their continuity. Both versions stand 55 meters tall and weigh 25,000 metric tons, sharing similar physical traits and a menacing presence. However, Godzilla vs. Megaguirus introduces subtle design changes like a smaller mouth and flatter face, and emphasizes Godzilla’s physical strength and strategic intelligence in battling the fast and agile Megaguirus. Despite mixed reviews and some criticized CGI, the film is noted for its intense monster battles and practical effects, contributing to the evolving legacy of Godzilla through incremental design and storytelling tweaks.

Everything about this suit is pronounced, from the fangs to the spiky dorsal plates to the ears. It’s less muscular than the Heisei-era suits, walking with a slight crouch and bearing no real heroic countenance outside of his willingness to tear apart any monster in sight. At this point, nearly every Godzilla film served as a direct sequel to the 1954 film, so it makes sense that the monster would be shown as both a franchising heavyweight and a potential doomsday creature.

Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001)

Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001) stands out as a unique entry in the Godzilla franchise, blending supernatural fantasy with traditional kaiju action. The film reimagines Godzilla as a vengeful spirit possessed by the souls of World War II soldiers, making him more menacing than ever. In response, three ancient guardian monsters-Mothra, King Ghidorah, and Baragon-rise to defend Japan. The movie is notable for its darker tone, intense human drama, and spectacular monster battles enhanced by impressive special effects. It also shifts the usual narrative by portraying King Ghidorah as a heroic figure, a departure from his typical antagonist role. Despite some budget constraints, the film delivers a gripping story and revitalizes the Godzilla mythos with fresh design and thematic elements.

As one of the most physically imposing Godzilla suits, the changes here are obvious as well – there are no pupils in the eyes; its neck and long, muscular body appear terrifyingly unnatural; and the teeth make the monster look as angry as his destructive actions suggest (at one point, he pauses to move past a hospital with an injured young woman in it, only to suddenly destroy it with his tail out of spite). Director Shusuke Kaneko had previously overhauled the Gamera series with a trilogy in the ’90s that often surpassed the Godzilla films, and what he brings to Godzilla is a return to the uncontrollable malice of Godzilla’s initial appearance. Godzilla even dwarfs King Ghidorah here, a sure sign that he isn’t messing around.

Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla (2002) and Godzilla: Tokyo SOS (2003)

Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla (2002) revitalizes the classic Mechagodzilla saga by introducing Kiryu, a cyborg built from the original 1954 Godzilla’s skeleton, piloted by Akane Yashiro to combat a new Godzilla threat. The film balances action-packed battles with a human element, exploring themes of memory and identity as Kiryu’s connection to the original Godzilla causes unexpected complications. It serves as a solid, accessible entry in the Millennium series, praised for its monster designs and pacing, and sets up its sequel effectively. Godzilla: Tokyo SOS (2003) continues this storyline, featuring a dramatic showdown involving Godzilla, Kiryu, and Mothra, with emotional stakes heightened by Mothra’s sacrificial role and the intertwining of human and monster narratives, making it a notable follow-up that deepens the franchise’s mythos.

For a film in which Godzilla takes on a Mechagodzilla that has been constructed around the skeleton of the original 1954 monster, references to the first film are necessary: Godzilla is given his initial gray color; his pointed ears; his harsh, scaly pattern; his large fangs; and his misshapen spine. There are some more modern touches as well, creating – like these film’s chaotic Mechagodzilla – an amalgamation of past and present.

Godzilla: Final Wars (2004)

Godzilla: Final Wars (2004) is a high-octane, action-packed entry in the Godzilla franchise that celebrates the King of Monsters’ enduring legacy. Set in a near-future world besieged by alien invaders known as the Xiliens and a host of rampaging monsters, the Earth Defense Force releases Godzilla from his icy prison to combat these threats. The film features Godzilla battling a parade of classic kaiju across the globe, culminating in an epic showdown against the formidable Monster X, who transforms into Keizer Ghidorah. Despite its fast pace and sometimes chaotic tone, the movie is a bold, energetic tribute to Godzilla’s 50-year reign, blending sci-fi elements, mutant super soldiers, and intense monster battles to reaffirm Godzilla as an unstoppable force.

This 50th-anniversary film has some of the touches of the original, but for the most part, it seems like a direct antithesis. Lean in arms, legs, and torso and with a smaller head, this Godzilla is less of a bringer of death and more of an action figure. It fits the purposes of the movie, though, which is primarily a parade of monsters being taken down by the King of the Monsters over the course of two hours.

Shin Godzilla (2016)

Shin Godzilla (2016) reinvents the iconic monster with a fresh yet familiar approach, depicting Godzilla as an ever-evolving, terrifying force of nature that emerges from Tokyo Bay and wreaks havoc on the city. The film uniquely blends intense political drama with disaster spectacle, focusing on the bureaucratic and military response to Godzilla’s rampage. Notably, it draws thematic parallels to real-life nuclear disasters, particularly Fukushima, adding a contemporary political allegory to the narrative. The creature’s design and abilities, including destructive atomic rays and a menacing purple glow, emphasize its otherworldly menace. Ultimately, the film portrays a coalition of human ingenuity and international cooperation to subdue Godzilla, underscoring themes of resilience and adaptation in the face of unprecedented threats.

Written and co-directed by the creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion, Hideaki Anno, Shin Godzilla returned Godzilla to his status as both a terrific force of nature and pure disaster metaphor. Though it goes through several stages of evolution throughout (most famously, the relatively little blood-spewing tadpole that wriggles through Japan), the most famous form is the glowing, disfigured behemoth with a jaw that unhinges for its atomic breath and that wields an abnormally long tail. It’s a design that quickly caught on with audiences (there’s even a theme park where you can zip line straight into a replica of its maw).

Godzilla (2014), Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019), Godzilla vs. Kong (2021), and Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023)

The MonsterVerse revitalized Godzilla’s legacy with a series of films and a TV show that redefined the iconic monster for a modern audience. The 2014 film Godzilla rebooted the character’s origins, introducing the MUTOs and the secretive Monarch organization, setting the stage for a new cinematic universe. Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) expanded this world by showcasing Godzilla’s dominance over other Titans, including the formidable King Ghidorah, and solidifying his role as the “King of the Monsters.” In Godzilla vs. Kong (2021), the long-awaited clash between two legendary Titans unfolded, culminating in their alliance to defeat the mechanized threat Mechagodzilla. The 2023 Apple TV series Monarch: Legacy of Monsters further explores the MonsterVerse, delving into the human side of the Titan saga and expanding the lore surrounding these colossal creatures. Together, these entries demonstrate how incremental design and narrative developments have kept Godzilla relevant and captivating across a decade of storytelling.

Though the Godzilla of the Monsterverse may look similar across the four movies and TV series that he’s appeared in, there are changes for devotees to appreciate. He retains his bulky frame and boxy, crocodilian head throughout, but one can notice a slight change in height from the 2014 film to King of the Monsters, along with differences in the back plates as a result of damage and its healing process. In Monarch, before he sustained any damage from the military’s attempts to kill him, we also get to see little bits of dirt and earth and moss that have accumulated on a prehistoric creature of his size.

Godzilla Minus One (2023)

Godzilla Minus One (2023) marks a powerful return to the franchise’s roots, set in postwar Japan and focusing on the psychological aftermath of World War II. The film follows former kamikaze pilot Kōichi Shikishima, who struggles with survivor’s guilt as Godzilla, mutated and empowered by atomic bomb tests, rampages toward Tokyo. Praised for its intense human drama and terrifying creature design, this installment is noted for its detailed digital rendering of Godzilla, making it one of the most ferocious and dynamic versions yet. Celebrated by critics and audiences alike, it stands as one of the best Godzilla films to date, earning numerous accolades and becoming the highest-grossing Japanese Godzilla movie.

The Godzilla Minus One design seems to spring from two sources: It retains a lot of the scars and grotesque textures of the original film, but its head and musculature seem to recall the Heisei Godzilla, which is also internationally recognizable. The burns that occur on it make for a nice touch, too – it’s a beast built out of nature, anguish, and mankind’s hubris, so a visibly pained form is fitting. Overall, it might not look like something totally new, but no Godzilla ever really does. Instead, over the last 70 years, the designs have been mixed and matched, ending up with many variations throughout that amount to one truly unkillable character.

How did tiny design tweaks keep Godzilla relevant for over 70 years

Tiny design tweaks have kept Godzilla relevant for over 70 years by continuously adapting his appearance to suit the evolving demands of filmmaking technology, storytelling, and audience expectations. Each new film introduced subtle changes-such as more flexible suits to allow dynamic movement, adjustments to the size and shape of his head and dorsal plates, and variations in eye expression-that enhanced Godzilla’s presence and emotional impact on screen. These incremental updates balanced maintaining the iconic core look with fresh elements, preventing the character from feeling outdated. For example, the original 1954 design featured a bulky, dinosaur-inspired suit with expressive, radioactive eyes, while later versions introduced stockier builds, more human-like eyes, or jagged dorsal fins to reflect shifts in tone from menacing to heroic or vice versa. Technological advances, like the introduction of animatronics in the 1990s and CGI in recent decades, also prompted design evolutions that kept Godzilla visually compelling. Even drastic departures, such as the 1998 American Godzilla, were part of this ongoing process, though not always well-received. Overall, these tiny, thoughtful design changes allowed Godzilla to evolve with the times while preserving his status as a cultural icon.

How did practical needs drive the minor design tweaks for Godzilla

Practical needs have been a major driver behind the minor design tweaks for Godzilla throughout the decades. Production designers and filmmakers often had to adjust Godzilla’s appearance to fit the technical and logistical constraints of each movie. For example, tweaks to the suit-such as modifying the fins, altering the foot shape, or making subtle changes to the face-were often made to improve the actor’s mobility, enhance the suit’s durability, or allow for more expressive movement on screen.

Additionally, changes were sometimes dictated by the demands of shooting environments or special effects integration. For instance, building sets on soundstages with practical effects required Godzilla’s design to be compatible with the physical limitations and visual requirements of those environments, which led to minor but meaningful adjustments in his look and construction.

Ultimately, these tweaks were the result of on-the-fly problem-solving to ensure Godzilla could “work” in a given scene, whether that meant better movement, easier integration with visual effects, or simply adapting to new filmmaking technologies.