Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron twists grief into a feverish dreamscape of warring herons and crumbling empires-a madcap sign-off from animation’s wildest visionary.

It’s been 10 years since The Wind Rises, the movie that fans of Japan’s famed Studio Ghibli assumed at the time would be the final project for Hayao Miyazaki, director of classics like My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away. But Miyazaki – who has famously retired multiple times without noticeably stopping work – has returned, at age 82, with another animated feature: How Do You Live?, known internationally as The Boy and the Heron. And while its very long development time strained Studio Ghibli’s resources, it’ll make back its budget quickly, just from the same people going back to rewatch it over and over again until they finally get what it’s all about.

After just one viewing, it seems that the only question Miyazaki is willing to answer for certain is why How Do You Live? wasn’t marketed at all. Up until the premiere, there were no trailers or advertising campaigns promoting the new Ghibli production, because when taken out of context, any scene or shot from this movie would only confuse audiences. The cutesy, human-sized, man-eating parakeets and a gaggle of rubbery grandmas who seem to have pudding for bones are just some of the things that probably made Ghibli’s marketing department cry.

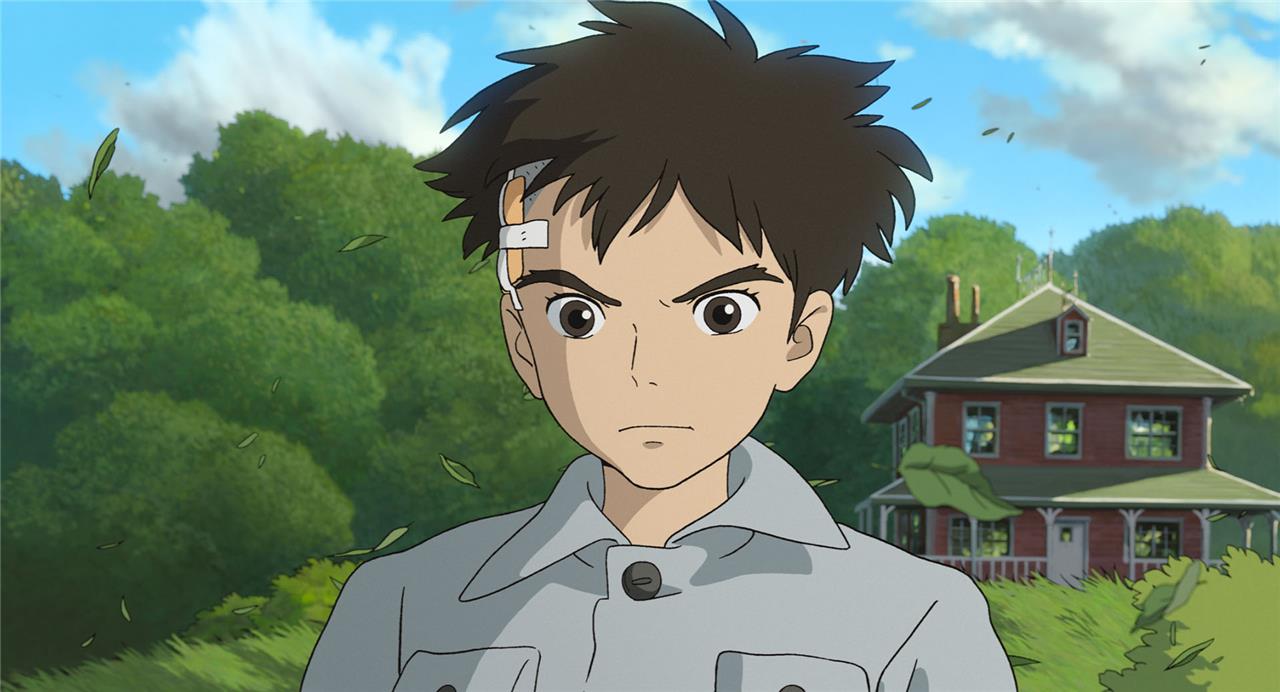

Let’s take it from the beginning. In World War II-era Japan, a young boy named Mahito moves to the countryside after his mother dies and his father marries his late wife’s sister, Natsuko. Suddenly, a gray heron starts harassing Mahito, finally speaking with a human voice and telling him his mother is alive. Mahito follows the bird to a strange tower built by his great-uncle and enters another world where he looks for his birth mom, tries to save his stepmom, and generally deals with fantasy challenges as he finds a new maturity.

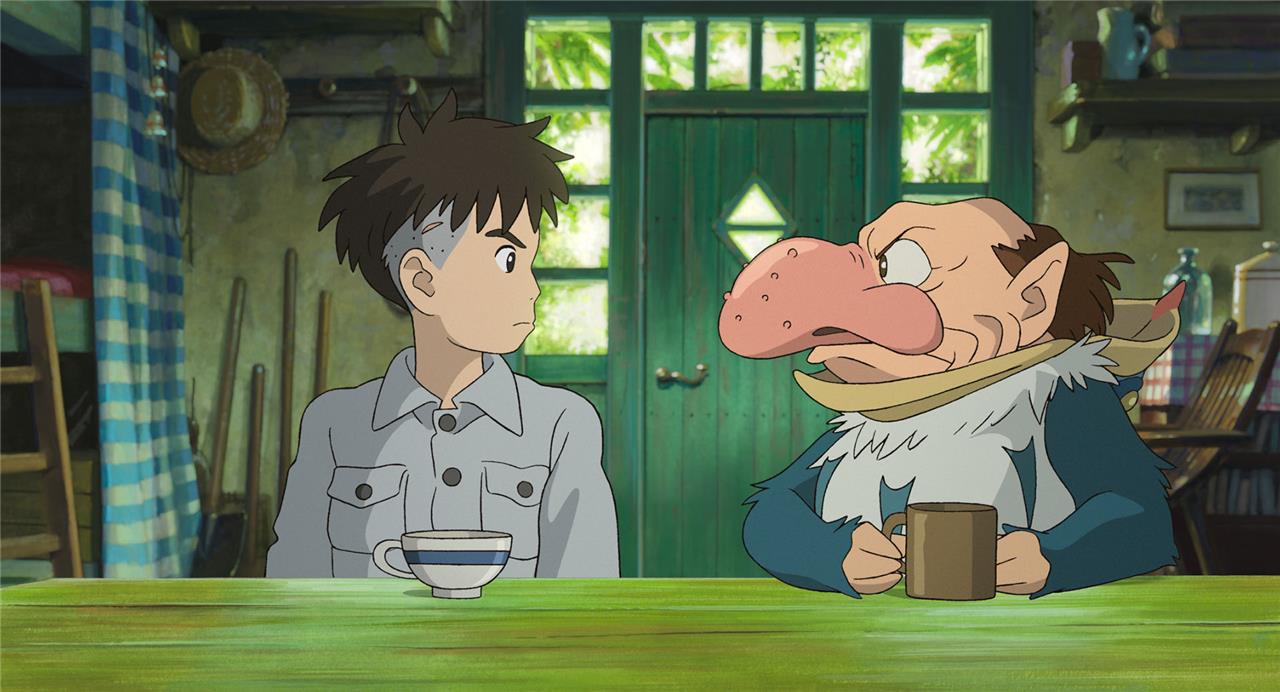

On the surface, all of this is par for the course for a Miyazaki film, with trace elements from Spirited Away,My Neighbor Totoro, or Kiki’s Delivery Service. The confusion starts when viewers try to square that with the parakeets, causality-breaking out-of-time characters, and the heron turning out to be a small gnomelike man wearing a living bird like a suit. Could all those elements be purposeful trolling from a director known for his, to put it delicately, acerbic personality? Maybe, but there seems to be a statement behind the madness: It’s as if Miyazaki is declaring, “This is my life’s work. I don’t care if you’ve enjoyed it. Goodbye.”

How Do You Live? seems to be referencing a number of previous Ghibli movies. Mahito moves away from the city because of his mother, much like Satsuki and Mei in My Neighbor Totoro. The tower that leads Mahito to another world seems to be alive and impossible in its architecture, and with the added scenes of magical fire, it’s more than a little reminiscent of Howl’s Moving Castle. But the most important echo is of The Wind Rises, the previous “final Miyazaki film,” which is also set around WWII and deals with the theme of creation – and how it so often goes hand in hand with destruction. How Do You Live? returns to that idea, but it feels more like Miyazaki is talking about himself and his own creative process.

A few things suggest that Mahito is meant to represent Miyazaki himself. In a profile about the writer-director, the BBC wrote that Miyazaki also had a strong bond with his mother, and that during WWII, he evacuated to the countryside with his father, who made parts for fighter planes, just like Mahito’s dad.

There’s also the fact that Mahito is deeply angry for most of the movie, in the same ways Miyazaki is. Miyazaki is more than a curmudgeon: In numerous interviews, he appears to be cynical and even deeply nihilistic. He’s a lifelong environmentalist who often gives the impression that he does not believe in the long-term survival of our species in the face of technological and industrial advancement. That theme is especially evident in his film Princess Mononoke, where humans (in an on-the-nose metaphor) murder a forest god in the name of progress. Mahito doesn’t exhibit any hatred for modernity or technology, but he does hold on to the comforting world of the past.

The title How Do You Live? refers to Genzaburō Yoshino’s 1937 novel of the same name – Miyazaki’s favorite childhood novel – which Mahito finds and reads in the movie. The book tells the story of a 15-year-old boy in prewar Japan (essentially another world, compared to the chaos of WWII and the postwar period) who exhibits pluck and courage, and wants to learn more about the world around him. It’s an old-fashioned kind of story from a different time, one that may not have a place in today’s world.

Then there’s the connection between Mahito and the world of Japanese mythology. For example, the numerous references to how Mahito’s stepmom Natsuko looks just like his dead mother seems to be foreshadowing a later tragedy: Her disappearance into the fantasy world. It could be a reference to the myth of Ame-no-Wakahiko and Ajisukitakahikone, which teaches us that it’s bad luck to comment on the similarities between living and dead people. Ame-no-Wakahiko also died in circumstances involving a bow, an arrow, and a bird, which are reflected in Mahito’s weapon of choice in the movie and his heron companion. There’s also a scene where Mahito is led to his pregnant stepmom behind a curtain, and he breaks the rules by peeking around it, which almost leads to disaster. That scene shares some surface similarities with the myth of Princess Toyotama and Hoori.

Just like Yoshino’s novel, these myths represent a bygone era – an idea that seems significant, given how the fantasy world of How Do You Live? is aging, crumbling, and decaying. It’s tempting to look at these themes as Miyazaki reflecting on his own mortality, and the disappearance of his own era.

The film’s fantasy elements look absolutely beautiful, and they naturally include shots of the classic impossibly delicious-looking Ghibli food. But they come with a kind of wistfulness for days gone by, paired with a full, unsentimental realization that there’s no getting them back. Which all feels like a director taking one last look at his career before bowing out. How Do You Live? has all the makings of a perfect swan song. Whether it really is that – whether Miyazaki’s retirement sticks this time – is something we won’t know for a while. In the meantime, his fans can watch this movie over and over, always finding something new and exciting in it. Final movie or not, it’s still a Hayao Miyazaki joint, and those have nearly endless rewatch value.

What are the main themes of The Boy and the Heron

The Boy and the Heron explores profound themes through Mahito’s fantastical journey during World War II Japan, blending grief with surreal fantasy. Hayao Miyazaki infuses the story with personal reflections on loss, creation, and human resilience.

Grief and Loss

Mahito grapples with his mother’s death in a fire, leading to self-harm and isolation from his new family. His adventure offers closure via encounters with alternate versions of loved ones, emphasizing healing through acceptance rather than resurrection.

Cycles of Life and Death

The film depicts birth, growth, decay, and reincarnation via a collapsing tower world sustained by blocks stacked without malice. Mahito rejects perpetuating this cycle, choosing real life’s imperfections over a “perfect” fantasy realm.

Creation and Responsibility

Metafictional elements critique world-building, warning against godlike control without understanding consequences, as seen in the Parakeet King and corrupted pelicans. It urges balance in art and life, echoing Miyazaki’s career-long motifs.

Moral Choices

Inspired by the book How Do You Live?, it poses how to live amid conflict, advocating resilience, alliances, and rejecting violence or power’s temptations. Everyday decisions matter in building a conflict-free world.

How does grief shape Mahito’s journey

Grief profoundly shapes Mahito’s journey in The Boy and the Heron, driving him from isolation to growth through a fantastical confrontation with loss. His mother’s death in a hospital fire during World War II leaves him withdrawn, lashing out, and struggling with his father’s remarriage to her sister, Natsuko.

Initial Isolation

Mahito’s pain manifests in self-harm, like injuring himself with a rock, and emotional distance from his new rural life, highlighting grief’s paralyzing early stages. The heron symbolizes this turmoil, luring him into a mystical tower realm where unresolved emotions take physical form.

Fantastical Confrontation

In the otherworldly tower, Mahito encounters Himi-a fiery girl revealed as a younger version of his mother-allowing him to process memories with love rather than just sorrow. He navigates cycles of life, death, and his great-uncle’s flawed utopia, rejecting escape for reality’s imperfections.

Path to Acceptance

By journey’s end, Mahito leads the heron instead of following it, signifying control over his grief and steps toward adulthood. He returns home, embracing messy healing over denial, mirroring Miyazaki’s themes of resilience amid loss.